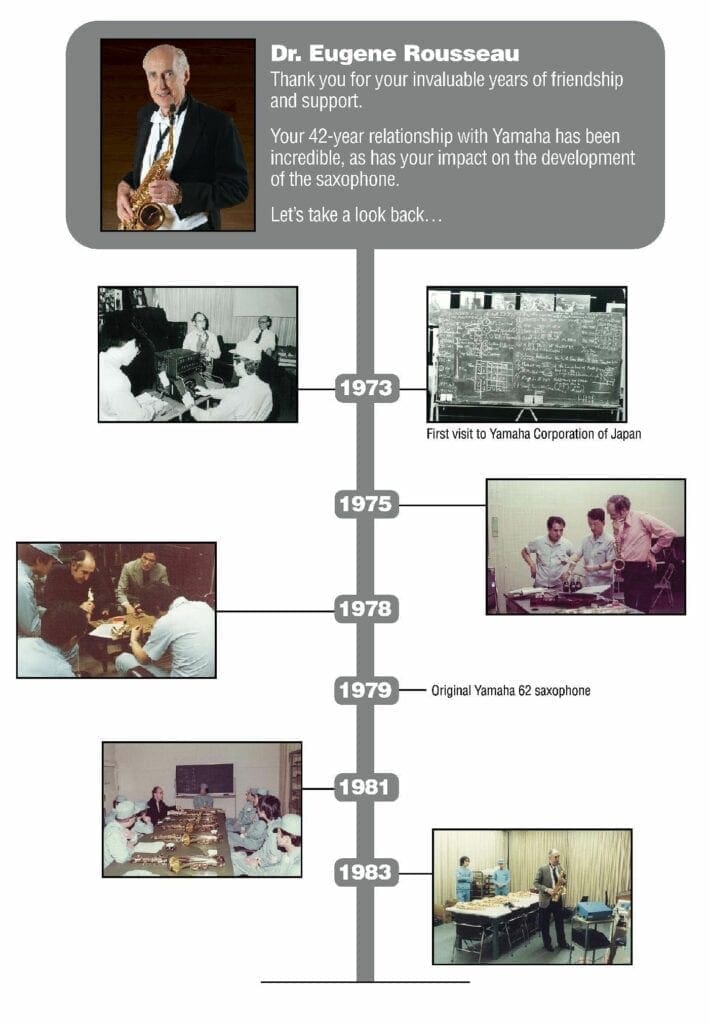

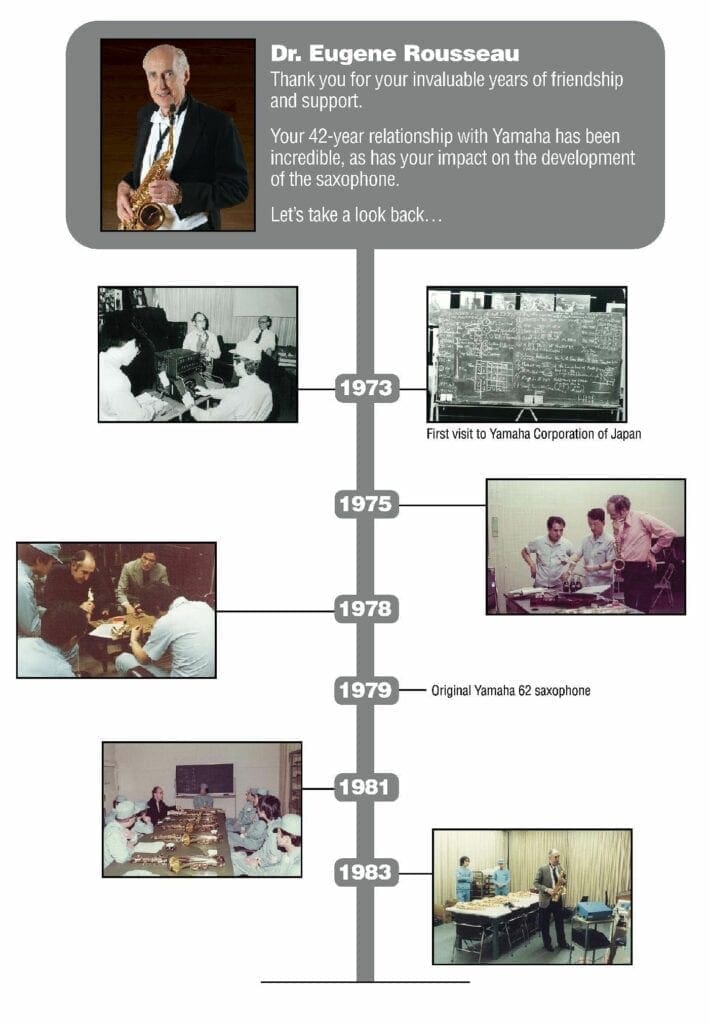

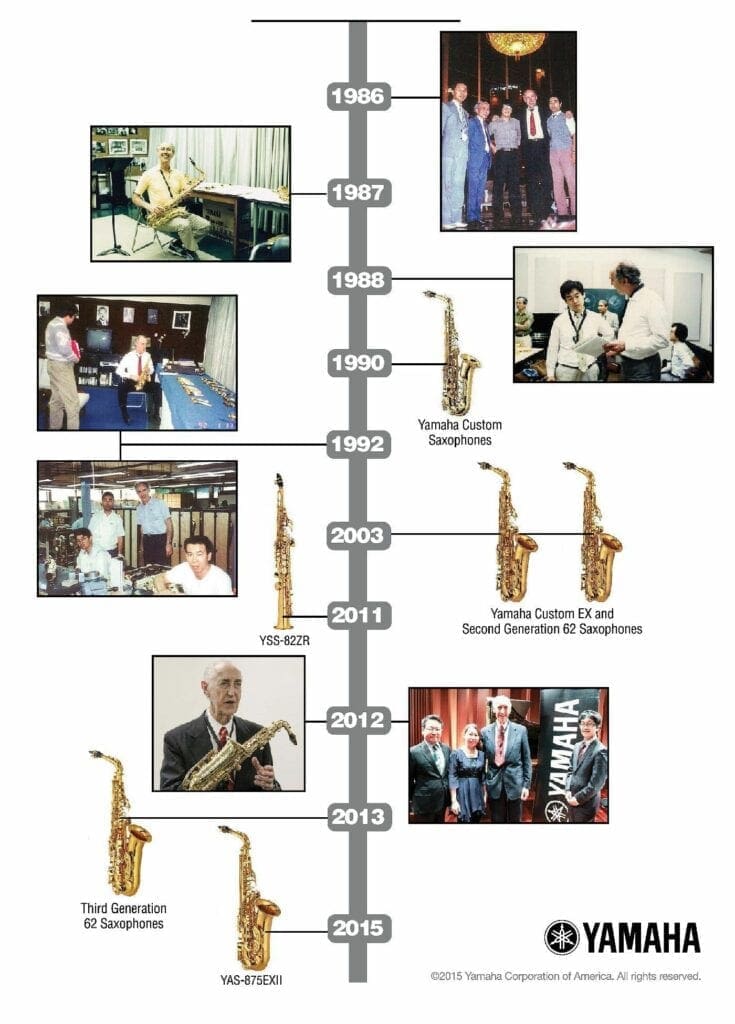

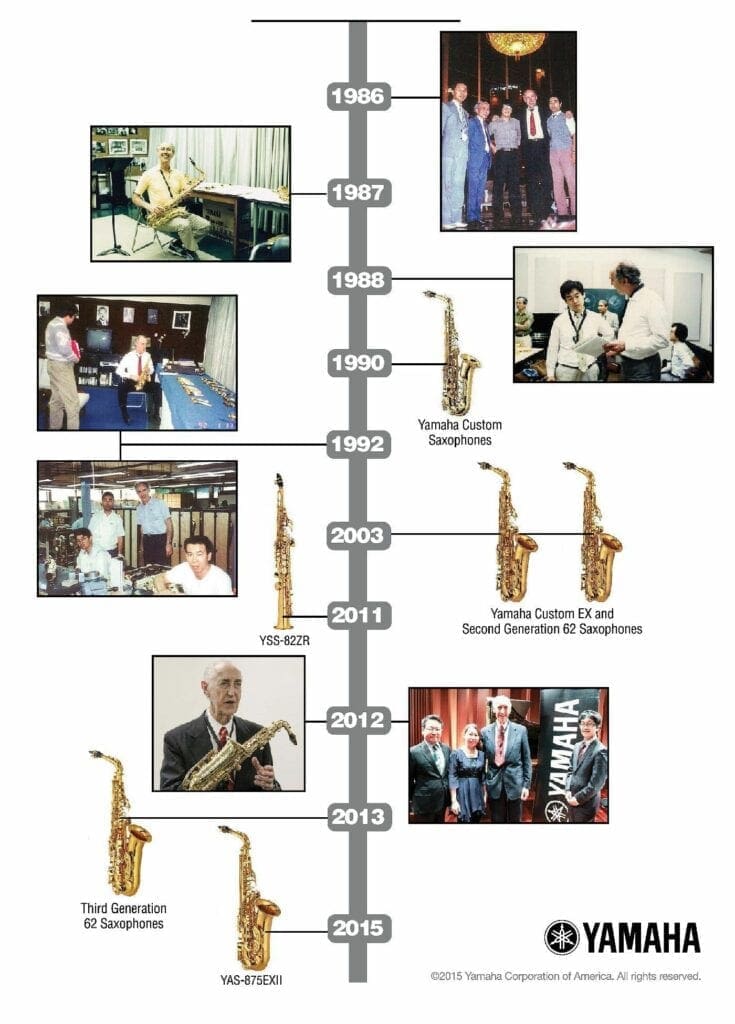

It is no secret that, during the last half of the twentieth century, Yamaha saxophones have become well known for the ability to perform at the very highest levels. It is also no secret that many other saxophone makers have attempted to utilize these same advances in their own models. With few exceptions, the Yamaha saxophone designs have influenced all saxophone manufacturing for the last fifty years. As Yamaha’s chief consultant for saxophone research beginning in 1972, Eugene Rousseau has had perhaps the greatest influence in the design of the modern saxophone of any player or teacher of his time.

Dr. Rousseau was introduced to Yamaha executives by Vito Pascucci, the president of Leblanc in the United States. During the 1970s Yamaha made Vito saxophones for Leblanc and sought to expand their market in the United States with their own models.

In a very real sense, Rousseau’s preparation for his association with Yamaha began in 1960 during his Fulbright study in Paris. Originally associated with the Leblanc Company since 1956, Rousseau was permitted by President Leon Leblanc to practice at the Leblanc Company every day and it was there he met acoustician Charles Houvenaghel. Houvenaghel (1880-1966) was the leading acoustical authority in Paris and had been involved with the development of clarinets and saxophones for Leblanc and other instrument makers. He designed the E-flat contralto and the BB-flat contrabass clarinets and Saxophone le Rationnel for Leblanc (called “the most important innovation to the saxophone in recent years” ).

After World War I, Georges Leblanc and his son Leon established the first full-time acoustical research laboratory for wind instruments in their Paris workshop. “They recruited the talents of Charles Houvenaghel, regarded at the time as the greatest acoustician since Adolphe Sax.” Rousseau and Houvenaghel quickly established a friendship and met almost every day for months. During these meetings, Houvenaghel taught Rousseau the practical aspects of wind acoustics and construction.

Eugene Rosseau relates, “We would talk about vent keys, emission of tone, various tapers, and many other interesting and important topics related to instrument construction. This was not really something I was going to do anything with; it was just a passing interest at the time. However, it proved to be the foundation for my work with Yamaha because he really got me interested in the acoustical aspect.”

“When I made my first trip to Japan I was absolutely fascinated, if not overwhelmed, by what I found. Yamaha’s research capabilities were outstanding. I felt the saxophone needed some upgrading and Yamaha had all of the tools necessary to do the job, as well as the determination and enthusiasm. In the saxophone division there were three full-time research and development persons; that is a large number for just the saxophone. There were other resources such as tuners, harmonic analyzers, and just about anything else needed to design a fine instrument.

Rousseau’s appointment as Yamaha’s chief consultant for saxophone research and development was concerned with mechanical, acoustical, and artistic components.

“The first area is the mechanical aspect of building a saxophone, including the keys and their function. The key action has to be free and not sluggish. The pads are also a part of this aspect. The second area is acoustical, which takes into consideration the body taper, tone hole placement and calculations, bocal taper, intonation, response, and tone quality. The third and most important aspect is the artistic. It is very possible to have an instrument that is theoretically correct on paper and seems to be good mechanically but, when the player picks it up, the instrument doesn’t feel right. This is a problem because the player must feel that the instrument will offer a viable means of artistic expression. We’ve also dealt with problems which were specific to the different-sized saxophones.“

It was a highly controlled environment. Rousseau would sometimes try the instrument with a blindfold to judge by sound alone while being carefully observed by instrument designers. Rousseau would also take prototypes and play them for months and then return to Japan with notes from which the engineers would create the next prototype. After nine prototypes and almost seven years, the release of the YAS-62 finally arrived in 1978. There was a great sense of accomplishment and the instrument would become one of the most popular saxophones in the world. More recent developments in SATB models have followed using the same process with similar acclaim.

In 2015, the Yamaha Corporation honored Dr. Rousseau at a celebration of Rousseau’s career at the University of Minnesota. Yamaha’s John Wittmann commented on the relationship with Rousseau. “He plays and lives with intention … He represents mastery of music and the saxophone, but he does it with a sense of humility. We’ve benefited having him as representative of our efforts to be innovative and creative while maintaining a high level of excellence with musical design.”

For more information on Eugene Rousseau’s history with saxophone acoustics and design, read Eugene Rousseau: With Casual Brilliance.

Wally Horwood, Adolphe Sax: His Life and Legacy (Baldock, England: Egon Publishers, 1983): 187-8.

www.gleblanc.com/historylindex.cfrn (now inactive)

‘” Gail Hall, “Eugene Rousseau: His Life and the Saxophone” COMA diss., University of Oklahoma, 1996): 59.